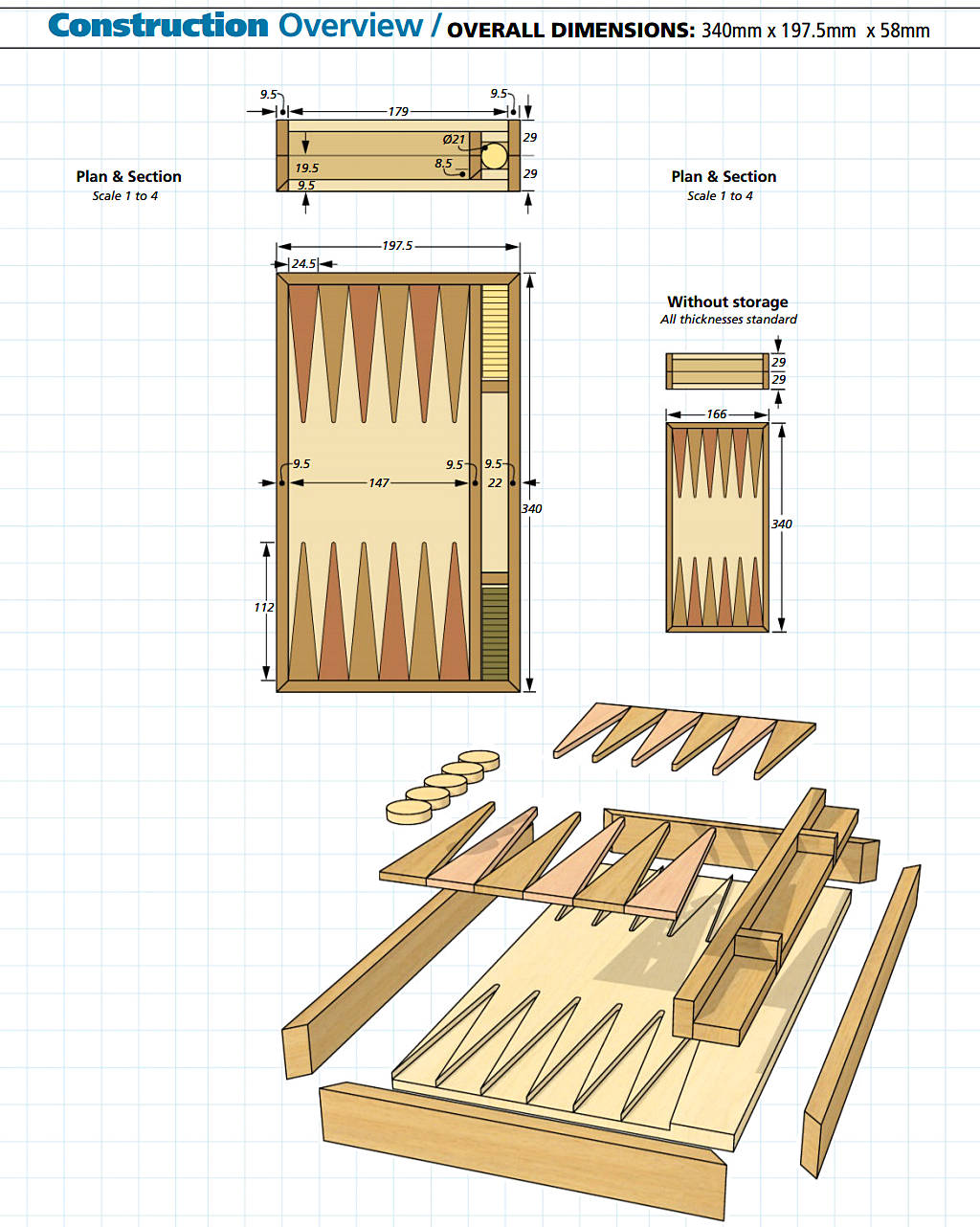

Anthony Bailey takes on the challenge of making his own game board.

The game of backgammon is one of the oldest board games and requires luck and skill to win. Each player has 15 checker pieces and there are two standard dice plus a special numbered dice thrown from a cup.

I thought making a backgammon board would be a challenging and interesting project. The case hinges and catches can be bought online, as can the dice that are required to play the game. You can also find a lot of information about game play and strategies for backgammon on the web.

Making the boards

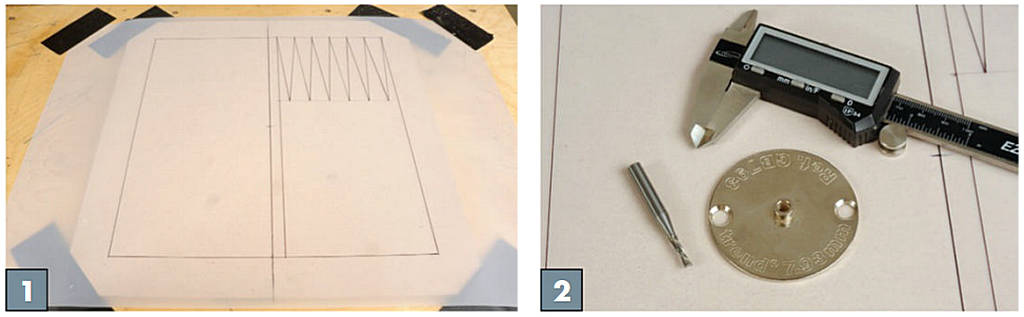

1. Start by copying the dimensioned drawing onto matte drafting film and tape it down, centred on a birch ply baseboard blank 400mm square. You only need one quarter of the pattern drawn out.

2. I used the Trend inlay kit because the spiral cutter is just 3.2mm diameter and comes with an equally small 7.93mm guide bush. The triangle shapes were too slender to use the kit as Trend intended, so instead of machining both the recesses and infill pieces to fit, these would have to be shaped by hand.

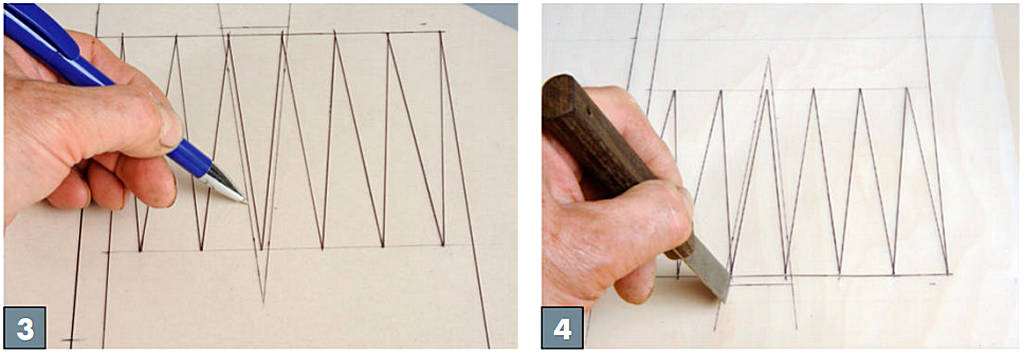

3. The guide bush allowance is approximate due to the diameters of the cutter and guide bush. Drawing it out on the drafting film with an ‘overrun’ at the outer edge allows you to design the template required.

4. A sharp knife is used to ‘prick’ out all the key positions on the birch ply baseboard. This allows accurate positioning of the routing template. To do all four ends, turn the drawing around 180° and mark, flip it over and mark again, then turn it around 180°. Align it each time using the comer ‘prick marks’.

5. Draw the triangle shape, including the guide bush allowance, on 6mm MDF. The fence is a piece of waste ply stuck down with double-sided tape. It is positioned by lining up the static cutter against the pencil line at both ends, then positioning the fence against the router base and pressing down firmly to fix it.

6. To machine the overrun end of the triangle, the fence batten is similarly placed. As the router could cut into the template, although it is not critical, I used a carefully positioned finger to pull the router base firmly against the fence.

7. Having ‘pricked out’ the key board positions, the shape of each half of the board plus the centre waste allowance is carefully marked out with a fine-edged pencil.

8. The template is placed over the first triangle position – note the two small knife marks being used to set it accurately. A template fence of ply is stuck in position with double-sided tape once the template is aligned both for perpendicularity and projecting over the board correctly, then screwed onto the template ready for creating all the recesses.

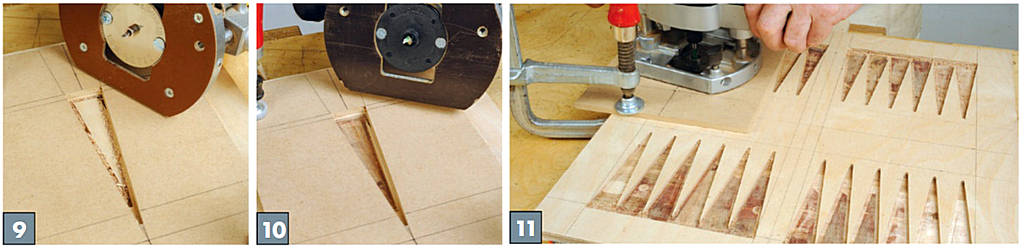

9. The first recess is machined in outline; some ply will need to be removed at the narrow tip as well. The cut depth is fractionally less than the inlay thickness to allow for flush sanding later.

10. The bulk of the recess is taken out I using a larger-diameter straight cutter and guide bush set at or fractionally above the depth of the outline cutter. Note that the guide bush offset should not bring the cutter closer to the template edge than the outline cutter, or the recess shape will get damaged.

11. Machining the last recess, note I that two clamps are used each time, thus avoiding the template moving under machining stress. The slight height variations in each recess are not important at this stage.

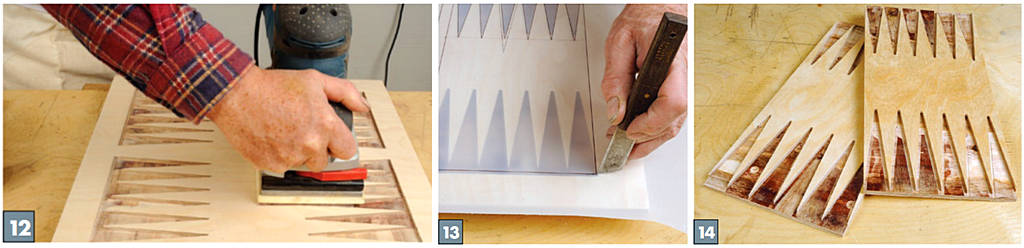

12. The whole surface is sanded I evenly. Work from side to side to avoid catching on the pointed shapes. Once the surface is clean and smooth it should be sprayed with clear lacquer to keep it clean and light in colour during subsequent operations.

13. Reattach the drawing and mark the corners ready for cutting the boards apart. This must be done accurately; a tablesaw is best, but alternatively it could be cut and planed by hand.

14. Here are the machined boards ready for their infill pieces. The points do not reach the ends because they are slightly over-length to allow for final trimming.

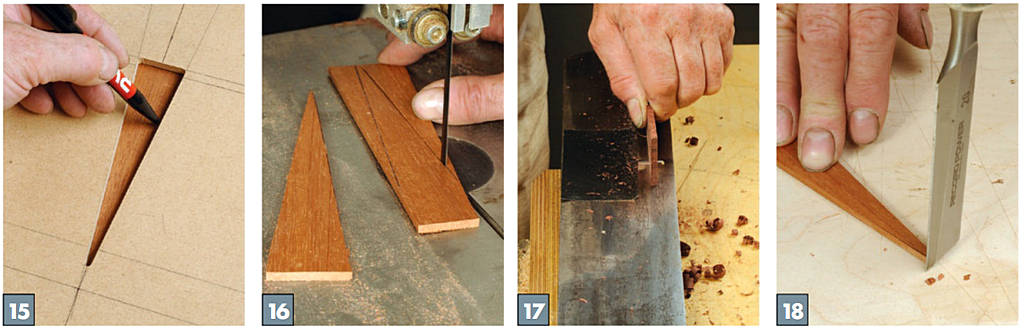

15. The template can be used as a crude method of drawing out the infill pieces on your chosen hardwoods. A slender-tip ball or rollerball is needed to get into the edges. Twelve pieces of each of the two coloured woods will be required for this.

16. Cut them out roughly on the bandsaw, ensuring you have drawn the grain running parallel with the shape – not at an angle, as it may look odd and complicate trimming them due to grain angles.

17. The next operation is interesting; using a technique that I find useful for small sections, each triangle is pushed over an inverted sharp hand plane, which is resting in the vice but not clamped, to avoid damaging it. It works well and very quickly, but keep your fingers clear of the blade and, just like an electric planer, most of the blade must be covered. Here I am using two layers of gaffer tape for safety.

18. Each piece is offered up to its own slot in turn, taking care to keep the correct alternating colour order. Trim each one on the plane until they line up – the point will overhang the recess end, so you need to ‘sight’ the fit. A sharp chisel is used to trim and round the ends. Try fitting again and trim as necessary until a tight all-round fit is achieved.

19. Alternate infills of the same colour and species are dry-fitted. A few light hammer taps will help bed the infills into place and ensure they look neat. They are plenty over-length to allow for re-trimming if needed.

20. Now the first set of alternate infills is glued in place. Start by applying glue to all meeting edges, then slide the infill towards the point, making sure it is bedded down well on the board.

21. Once the glue has dried, invert I the board and trim off the excess from the infills. Now repeat the whole infill sequence with the other wood, filling in the gaps in between. You need to have done the previous set first so that the overhanging infills don’t get jammed against each other.

22. Both boards are placed together against a batten placed shallow in the vice, acting as a stop. The boards are carefully and evenly belt-sanded level with 120 grit before using a random orbital sander and 240 grit to give a nice scratch-free finish. A clear lacquer is sprayed on to keep the surfaces clean.

23. A T5 technical jack plane and shooting knob, with a blade sharpened dead straight, is used to trim the board ends on the shooting board. Any correctly sharpened jack plane will do this job.

The checkers

24. Before making the case, try making the checkers – the pieces that are moved on the board. These are made from 21mm-diameter hardwood dowel. Standard dowel may not be quite round, but some careful sanding will take care of this. A jig is required for cutting the checkers. I decided to use the brilliant little Z-Saw mitre saw set. It is very precise, quick and safe; on a powered machine this would not be so.

25. Two length stops are fitted to the jig: one determines the checker thickness, the other is for the Z-Saw mitre device to press against – between the two you can achieve repeatably accurate results. You need a minimum of 30 checkers, plus spares, but the production rate is actually quite fast using the finetoothed pullsaw.

26.The counter faces are sanded on a sheet of medium and then fine abrasive. The edges will still need a final de-fluffing. Spray the natural-finish checkers with a clear lacquer to prevent them from getting dirty.

27. Now dye the other set black and M leave them to dry, then re-dye them if necessary. Once they are fully dry, spray with more clear lacquer. All spraying operations must be done in a well-ventilated area, well away from naked flames.

The box lids

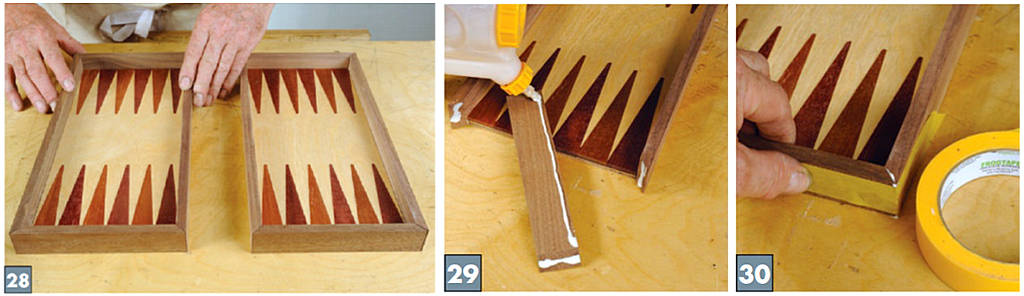

28. Normally, wide boards would be glued on and sawn down the middle to separate them afterwards, creating two matching lids. However, I had some walnut that was nearly at the right size, so I made each board lid separately. The butt mitres were carefully measured and cut, again using the Z-Saw mitre kit for very accurate cuts.

29. Glue is run along the lower face where it will meet the board and on the mitre faces. When assembled, the surplus glue can be removed without it marring the board surfaces, as they have previously been sealed with lacquer.

30. Masking tape was used to bind the corners closed, allowing the glue to exude. After that, a series of clamps were lightly applied to help close all possible gapping. The joints should then be tight enough to avoid needing any extra joint reinforcement.

31. Both outer faces are belt-sanded I together fora longer-and therefore flatter – surface when sanding. The edges are belt-sanded together in the vice for completely flush surfaces. Gaffer tape is used to maintain alignment. After that, all arrises are lightly broken and all surfaces sprayed with clear lacquer to seal them, then re-coated once dry. All that remains is the fitting of box hinges and catches.

32. Masking tape holds the box halves together. The hinge positions were marked and an engineer’s square and a marking knife used to complete the marking out.

33. A mortise cutter is set to just over the hinge leaf thickness and the recess is machined away. A sharp chisel is used to trim the ends and the hinge is checked for fit.

34. The hinge holes are drilled and screwed, then the hinges are carefully fitted without overstraining the brass. I always angle the screw heads so the slots form a pattern. The box stays closed thanks to 8mm diameter rare-earth magnets superglued into shallow holes.