This catchall shelf is the perfect home for all those things that don’t really live anywhere else. Curios, knickknacks, books and collections can all find a home here. This shelf will also introduce you to working with metal, even if you’re not a metalworker.

BY GORD GRAFF

For those of you who ask if working with steel is difficult my resounding answer is a definite no, and this project will show you how. The benefits of incorporating steel into a woodworking project are numerous. Its strength, endless design options and finishing possibilities make it an excellent choice to increase your design and construction approach.

No longer an outcast, steel and wood furniture has been widely accepted by designers and woodworkers alike who embrace a contemporary design.

Start with wood

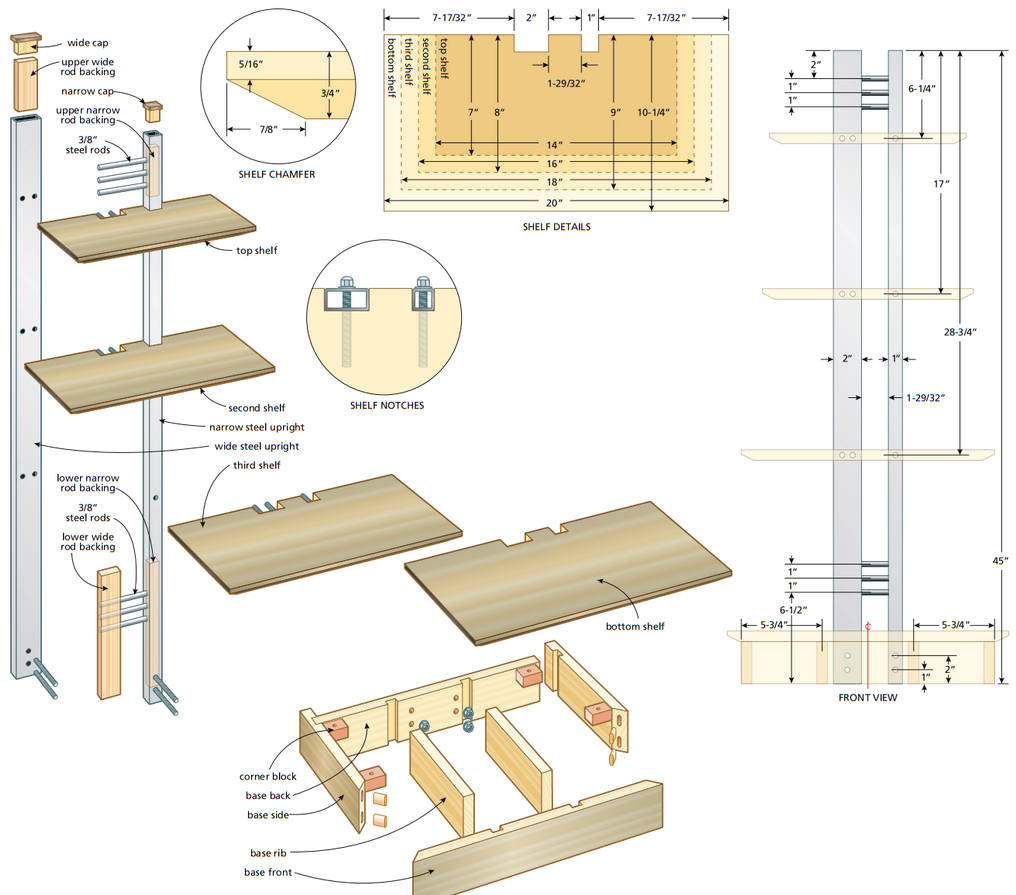

The choice of oak was not by accident. Ebonized oak’s grain produces a dramatic visual effect against the steel uprights. Edge glue enough 3/4″ thick oak to make the four shelves and put them aside to dry overnight in clamps.

Cut all the base trim parts to width, then machine the bevels on the front and sides of the base.

These bevels can be reinforced with biscuits, dowels, a spline, Dominos or whatever you have access to. I cut two 5 x 30mm slots in each corner with a Festool Domino.

Cut all the dadoes required in the base assembly, trim the parts to length and you’re ready to assemble the base. Check the base for square, wipe away any glue squeeze-out and set aside the glued-up base to dry overnight.

When dry, remove the shelf material from the clamps and cut the shelves to their finished length and width. Bevelling the underside of the shelves is next. A 25° bevel cut refines the look of the shelves and gives them a lighter appearance. Tilt the table saw blade to 25° and cut the shelves using a vertical table saw jig. Another option would be to use a chamfer router bit to remove most of the waste and follow up with a hand plane to fine tune the angle.

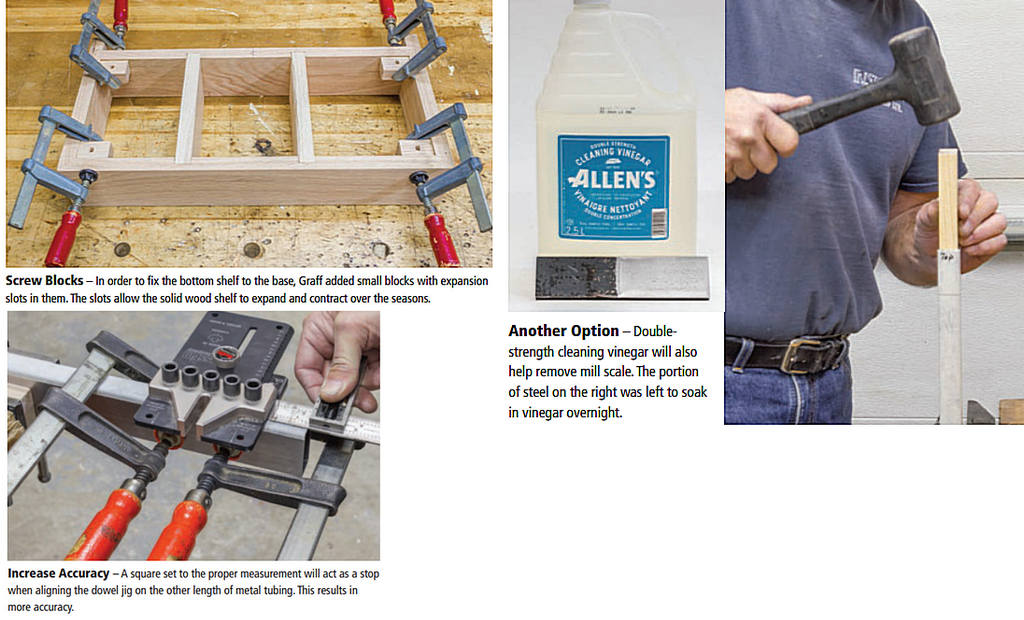

With the base assembly dry and out of the clamps, the next step is to glue and clamp blocks into each corner of the base assembly. These small blocks with their elongated screw holes will be used to attach the bottom shelf to the base and allow the oak to expand and contract with changes in seasonal humidity. The blocks are glued approximately 1/16″ below the surface of the base’s top edge to allow the screws to draw the bottom shelf tight to the base when tightened.

Turning to the steel

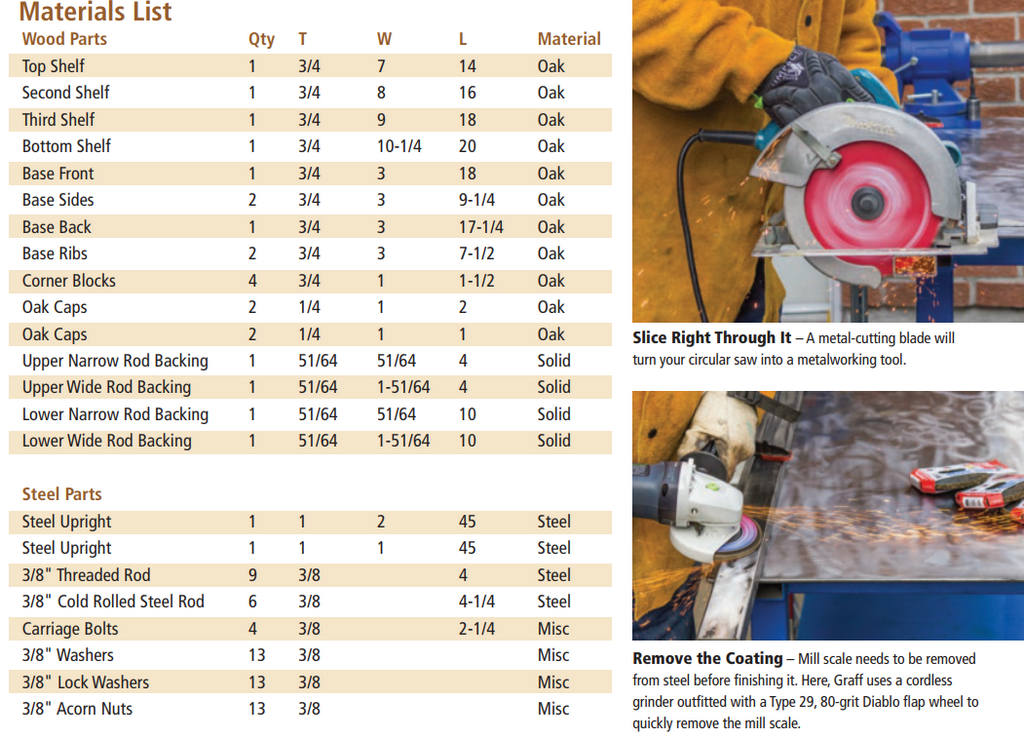

Putting aside the wood shelves and base, it’s now time to turn our attention to the steel portion of the project. Cutting steel has been made easy and effortless by the introduction of steelcutting blades for corded and cordless circular saws. I used my 30-year-old circular saw outfitted with a Diablo 7-1/4″, 48-tooth Cermet blade designed for cutting ferrous metals and stainless steel. Diablo makes a number of these steel-cutting blades for a wide variety of circular saw sizes and material thicknesses.

If you can cut wood with a circular saw, you can now cut steel studs, angle iron, flat bar, EMT conduit, all thread, plate and more using the same saw; it’s that easy. Clamp both pieces of tubing together and cut them to length.

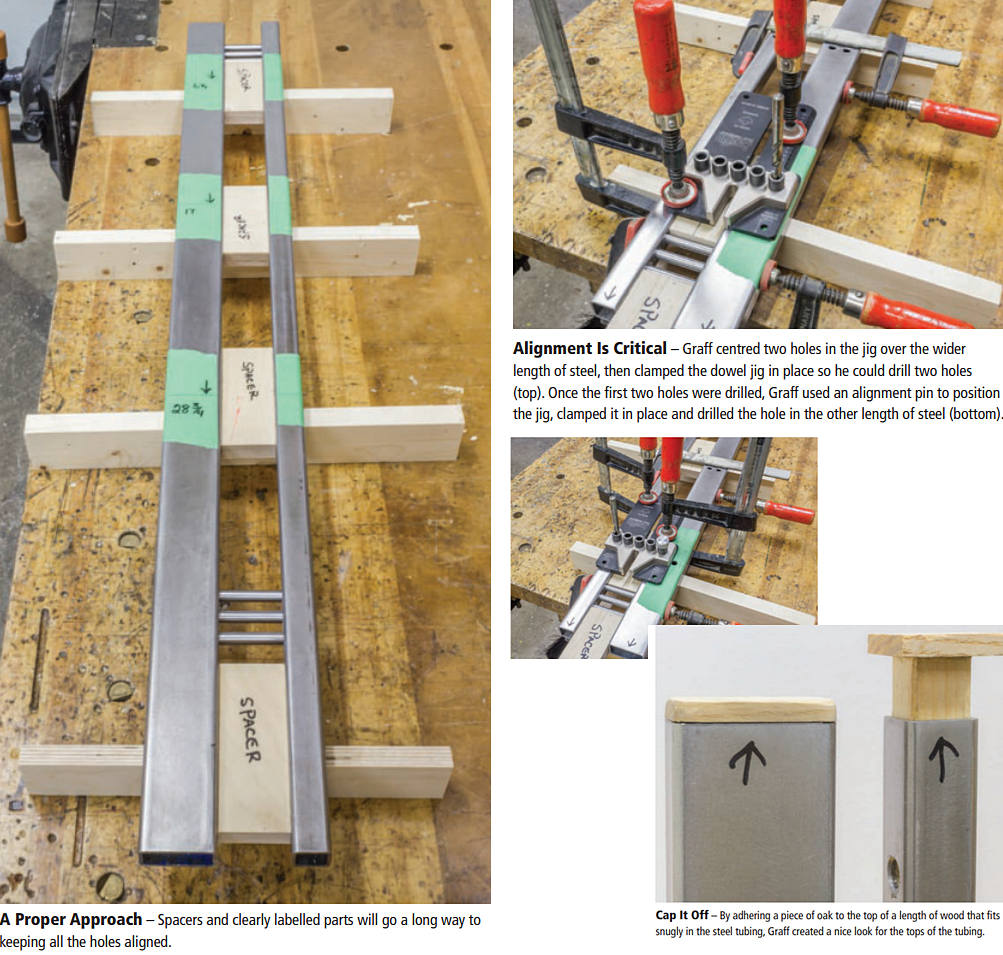

Hot rolled steel, including tubing, comes from the manufacturer with a coarse-looking coating on it. That coating is called mill scale and it’s a byproduct of the manufacturing process. The mill scale needs to be removed and there are several ways of doing that.

Here I’ve used a cordless grinder outfitted with a Type 29, 80 grit Diablo flap wheel that makes quick work of removing the mill scale.

At times, the mill scale coating is heavy and clogs up a flap disc. Here’s where a different method of mill scale removal comes into play.

Soaking heavily encrusted mill scale steel overnight in cleaning vinegar is an easy method to remove mill scale and it works great. Left to soak in vinegar overnight, this heavily encrusted coat of mill scale wipes off easily and can then be sanded with 120-grit sandpaper.

Cutting the 3/8″ threaded rod and steel rod is next, and that task is accomplished by using a hack saw, an angle grinder with a cut off disc or the circular saw and a steel cutting blade. When done, I milled some pine scrap material to fit snugly into both sizes of tubing. When drilled, the pine “backing material” creates pockets to capture the steel rods relying on a “friction fit” in the pine backing material to hold the rods in place. The wall thickness of my tubing is 0.100″ so the pine I milled was 51/64″ x 1-51/64″ for the 1″ x 2″ tubing and 51/64″ x 51/64″ for the 1″ x 1″ tubing. You’ll need one of each size of this material 4″ long for the installation of the rods at the top of the unit. Tap it into the top of each tube, setting it 1″ below the end of the tube. You’ll also need one of each size of this material 10″ long for the installation of the rods at the bottom of the unit. Tap it into the bottom of each tube, setting it 1″ below the end of the tube.

Drill some holes

It’s possible to drill all the holes required for this project by carefully measuring and marking each hole location and using a drill press, but a dowelling jig has built-in accuracy and reference surfaces, so that’s why I chose to use it. If you don’t have a dowel jig it’s not hard to make one. Use some hardwood and drill a few holes in the correct locations, then screw a hardwood fence to the jig.

You can either make a few jigs to drill the different holes, or make one with an adjustable fence and a few hole patterns in it.

Measure down from the top of the 1″ x 2″ rectangular tubing to the first 3/8″ hole location, clamp the dowelling jig in place, and set an adjustable square at the end of the tubing and square against the dowelling jig. With the adjustable square now set, go ahead and drill the three holes required for the rods, making sure you drill all the way through the wood in the tube but not through the other side of the tube.

Next, loosely clamp the dowelling jig onto the 1″ x 1″ square tubing and use the adjustable square to position the dowelling jig using the end of the adjustable square referenced off the end of the tube. Drill these three holes. By using an adjustable square as a reference, the holes in the 1″ x 2″ and 1″ x 1″ tubing are the exact same distance from the top edge of both tubes. Do the exact same procedure when drilling the holes from the bottom of the tubes. Although the measurement will be different, using this adjustable square method results in holes that are perfectly placed in both tubes.

Slide the rods into the tubing edges and mark the location of the holes in the face of the tube using painters’ tape. It’s now time to drill the holes in the face of the tubes to support the shelves. It’s important here to remember that you want the hole locations centred on both tubes. Once this is determined, measure the gap between the two tubes and cut four scrap spacers to fit snugly between the two tubes. Using my dowelling jig, my spacers were 1-29/32″ wide.

Clamp the spacers and the tubes together while drilling the three shelf hole locations. This way nothing moves out of place. Place the dowelling jig in position for drilling the top three holes, making sure that the jig is perfectly aligned with the edge of the 1″ x 2″ tubing and perfectly square to the edge of the tubing. Careful alignment here means that your shelf wrill sit level in use.

Drill the first two holes through the 1″ x 2″ tubing and remove the jig. Place the alignment pin or a spare piece of 3/8″ rod (not threaded rod) in the second hole you just drilled, square the jig again and clamp it into place. Now, if you’ve measured right and cut your spacers to fit your dowelling jig’s hole pattern, you should be able to drill a perfectly centred hole through the 1″ x 1″ tubing.

With that done, drill the next two set of holes using the same method, remembering to keep the tubes and spacers clamped together until you’ve completed the shelf hole drilling process.

Plugging the tubes

Plugging the top and bottom of the tubes is next and you can use some of the leftover material you used to tap into the tubes to catch the 3/8″ solid rod. Cut four pieces of 1/4″ thick oak a little longer and wider than the outside dimensions of each tube and epoxy them to 1″ long inner tube material. When the epoxy hardens, shape and sand the oak to fit flush to the outside of the tubing. You now have feet and caps for the tubing that can be easily inserted.

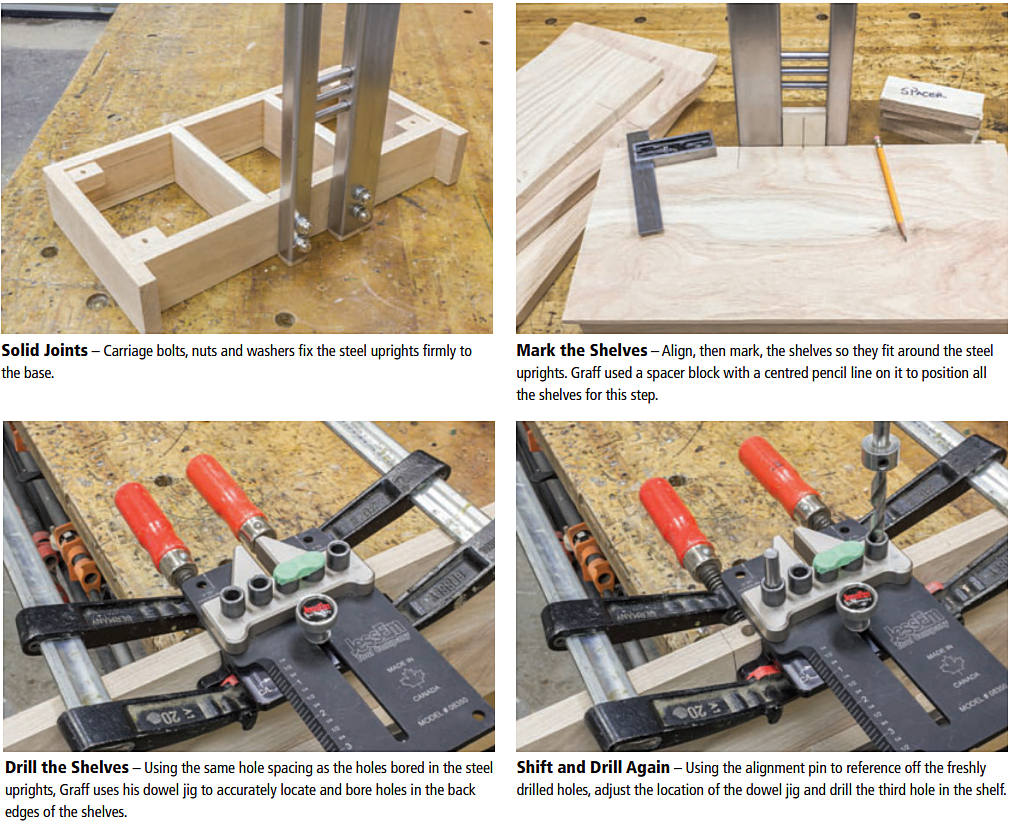

With the rods and spacers clamped together, install the tube feet then mark and drill the tubing for the 3/8″ carriage bolts that hold the uprights and base together. Align and clamp the uprights and base together, being extra careful here to make sure the uprights are perfectly square to the base before drilling the holes into the oak base. Drill the holes, install and tighten the carriage bolts.

Back to the wood shelves

Mark a centreline on one of the spacers and slip it between the tubes and the base. Mark the centre of each shelf and line it up with the centreline of the spacer. Using a square, mark the outside edge of the 1″ x 2″ tube on the oak shelf. This line will reference the dowelling jig to accurately drill the three holes for the 3/8″ threaded rod which holds the shelves in place.

Set the dowel jig to drill in the centre of the shelf and place the dowel jig on the reference line you just marked and clamp the dowel jig in place. Just like drilling the face of the uprights, drill the first two holes, remove the jig and insert the reference pin, re-clamp and drill the final hole. These holes are in the exact same position as the holes in the faces of the uprights, centred on the shelf. Repeat for the other two shelves. With the dowel jig removed, drill all shelf holes 3-1/2″ deep.

Slide the previously cut 4″ long pieces of threaded rod into each shelf hole and slide the third shelf assembly into the two uprights. Carefully mark the outside and inside edges of both tubes onto the oak.

These lines indicate the area that needs to be removed to a depth of 1″. Removing this material can be done at the bandsaw but I chose to use the table saw with a 3/4” wide dado set, set to the height of 1”. I installed two miter gauges and screwed an 8″ tall plywood fence between them that I can clamp the shelves to during each cut.

With the threaded rod in place, check the fit as you go. When the shelf fits nicely and the threaded rods don’t bind, move onto the other shelves. The bottom shelf requires no threaded rod so notch the shelf to fit.

With the holes drilled and the notches cut, countersink the shelf holes slightly. This countersink will capture any excess epoxy in the next step. The threaded rod holes should be 2-1/2″ deep from the edge of the notch. This means that when installed into the tubing, there should be 1/2″ of threaded rod protruding through the back of the tubing for the 3/8″ washer, lock washer and nut.

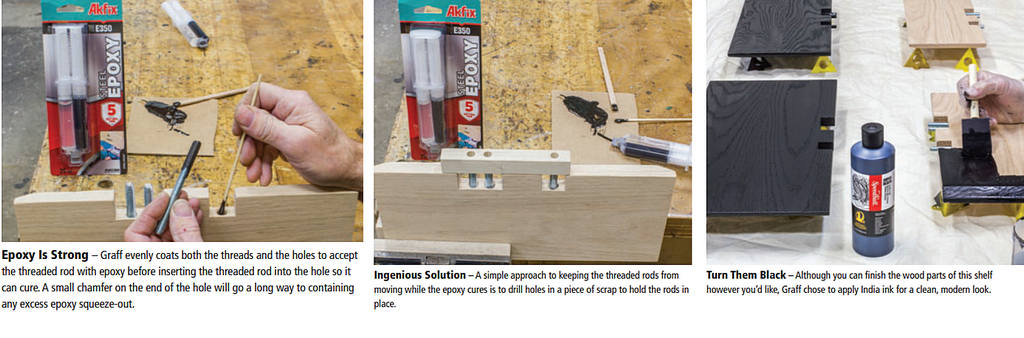

Securing the threaded rod

Akfix E350 two-part steel epoxy provides excellent adhesion between wood and steel and is perfectly suited for securing the threaded rod into the shelves. Mix according to the instructions and use a small stick to coat the inside wall of the hole. Place some epoxy on the threaded rod and insert it into the hole.

I cut and drilled three pieces of plywood using the same hole configuration as the shelf holes and slipped them over the threaded rods to hold them in place until the epoxy cured.

With the epoxy cured, check the fit of all parts. Install the uprights and shelves using the washers, lock washers and acorn nuts. The acorn nuts cover the exposed threaded rod ends and create a finished look.

Finishing

Dampen all the oak parts with a damp sponge to raise the grain and let them sit overnight. Lightly sand with 320-grit sandpaper to remove the raised grain and apply India ink using a foam brush. Let dry overnight.

Apply a second coat of India ink if required. When dry, topcoat the oak parts with three coats of water-based satin polyurethane, lightly sanding with 400-grit sandpaper between coats.

There are numerous choices when it comes to finishing the steel parts: powder coating, paint including a hammered finish, clear lacquer, paste wax, etc. It all depends on the look you’re after. Some choose to sand the steel to 1500 grit and higher to achieve a highly polished look. I chose to sand to 220 grit with a random orbit sander and sprayed the steel parts with three coats of automotive matte lacquer. However you choose to finish the steel parts, it pays to experiment first.

Many of the techniques and tools we use as woodworkers can easily be applied to working with steel, and the design and construction I benefits of incorporating steel into a project are numerous. Imagine the possibilities.