When it comes to cutting simple straight lines, the table saw is the champ! Now build your skill set with these three next-level techniques.

You use your table saw routinely for ripping and crosscutting wood in perfectly straight lines, guided by the fence or miter gauge. Tilt the blade or adjust the gauge, and you get straight bevels or mitered cuts.

No argument, that’s the table saw’s bread and butter. But beyond those basic techniques are several others you should consider adding to your arsenal of skills. Let’s take a look at three of the most useful ways to go beyond the basics.

Cove Cutting

Coves are common in molding, trim, picture frames, box components and more. Small coves, like simple coved trim, are easy to make with a router. But for wider, deeper coves for crown molding, box sides and other larger projects, you need either a shaper with large-scale cutters or a well-stocked trim supplier.

But you can also cut coves on your table saw. The process may seem tricky (and maybe a bit scary if you’ve never done it before), but it’s really just a matter of simple preparatory steps and the right guidance for your workpiece. The type of blade you use doesn’t matter, but a higher tooth count produces a smoother cut.

While coves are arcs, you still cut them in a straight line. The trick is orienting the workpiece at an angle so the saw cuts in a spiral to form the arc. You can do this with straight wooden guide pieces clamped to the saw at the appropriate angle, but clamping to a saw table isn’t always easy; there are some places on saws that clamps just won’t go.

Instead, consider a miter slot-based cove-cutting jig, such as the Rockier offering seen in the opening photo, that uses expandable miter bars to lock the jig into place. Its parallelogram design makes for easy alignment, while a vertical featherboard keeps workpieces pressed down securely during the cut.

To demonstrate, I’ll cut a cove measuring 5/8″ deep by 3½” wide, into a 1″-thick work-piece. I want the final coved workpiece to be 4¾” wide, but I’ll include a bit of extra at the edges to fine-tune the piece after coving.

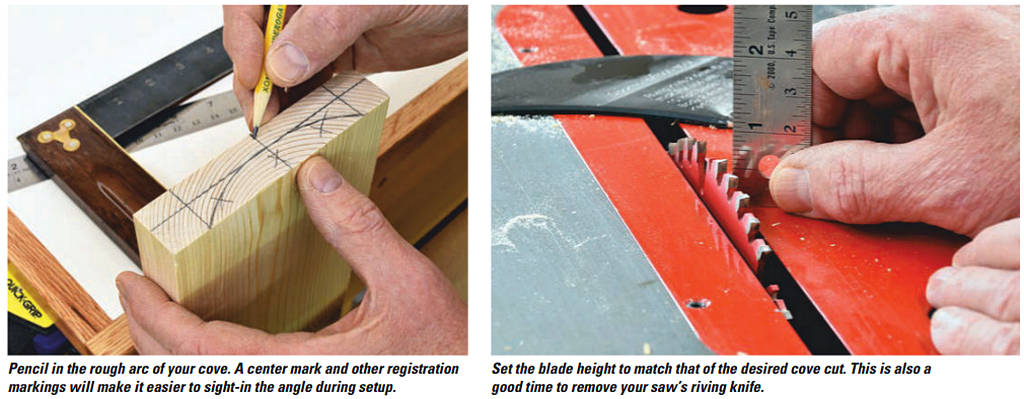

First, I mark the end of the workpiece. Here, I’ve not only drawn the cove but also a centerline, a horizontal line at the top of the arc and a pair of lines delineating the ends of the cove. These make it easier to set the correct angle on the saw.

Now I set the saw blade to the cove’s depth, in this case 5/8″ high. By the way, you can’t leave a riving knife in place when cutting coves, so that’s why I’ve removed it.

With the blade height set, I mark where the teeth exit and enter the throat plate, placing masking tape at the exact points where they come up and go down — tooth tips should just graze the tape. Note in the middle right photo that the exposed portion of the blade is actually longer than the marked cove on the workpiece.

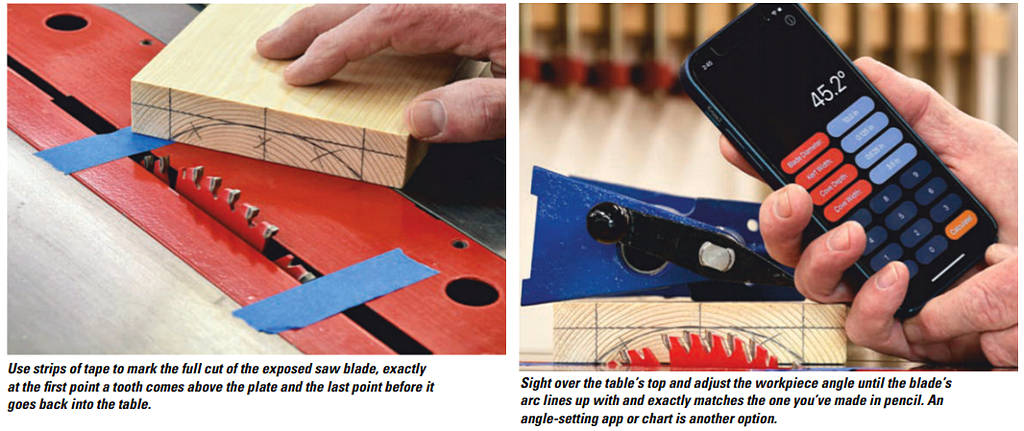

Next, I place the workpiece in front of the blade, with the feed angle matching my saw’s tilt; for my left-tilt saw, I’ll angle the feed from the left. Feed direction doesn’t matter for symmetrical cove cuts with the blade at 90 degrees, but it will matter for asymmetrical coves that require a tilted blade. More on that later.

I align the workpiece where the first tooth will contact the wood and then sight from the other side of the table. (Those vertical registration marks make this easier.) Now I can angle the workpiece and sight over the blade until the cove exactly matches the blade’s are.

By the way, there are easy-to-find angle setting charts and even phone apps on the Internet that calculate the correct feed angle for you.

Here, my exact calculated angle is 45.2 degrees, but I settled on an easily repeatable 45 degrees for my cove.

Without moving the work-piece (a weight, such as a pipe clamp, can keep it in place), I lay strips of tape along the workpiece edges to act as guides for jig placement.

When that’s done, I lower the blade.

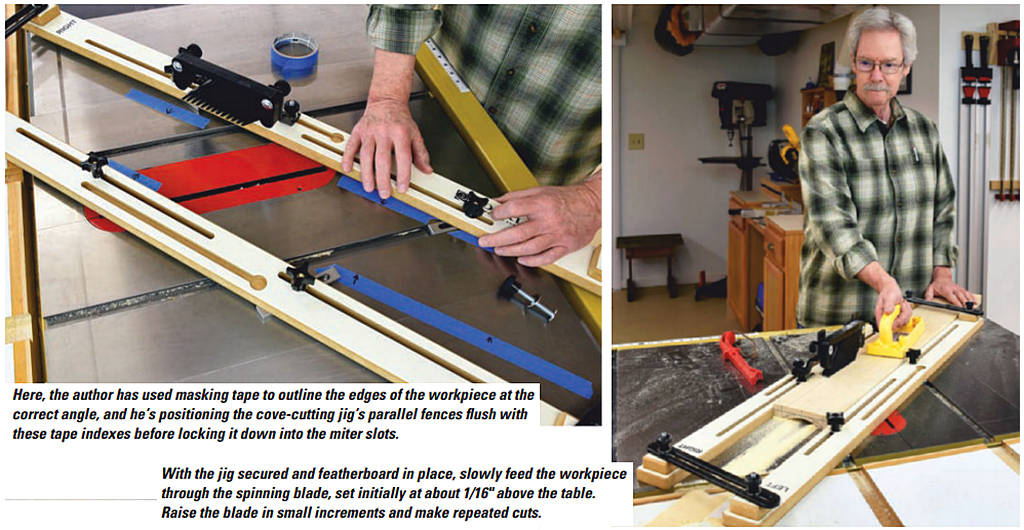

Now I loosen all knobs and place the jig on the table saw, aligning its inner edges to the tape. The miter bars are inserted into their respective slots, and I lock them down with one side

of the jig exactly on the tape edge. Then I repeat with the other side, locking the end bars to secure everything into a rigid parallelogram.

If you’re following along on your saw, set the workpiece inside the jig and check that it moves freely, adjusting the jig as needed. Finally, set the featherboard to hold the work-piece through the cut. Since you’re cutting across the blade, you’ll get resistance; the steeper the cut angle, the harder the push will be. Keep in mind, too, that hardwood will present more resistance than softwood. So cut in blade height increments of no more than 1/16″ at a time.

Now raise the blade and make the first pass. Push blocks are essential for this operation, as your hands pass right over the blade. After each cut, raise the blade 1/16″ and take another pass until you’ve cut to your layout line and the cove is complete. Feed a bit more slowly on the final pass to create a smoother surface.

If you plan to make more coves with the same setup, cut off a small piece at the end of the finished cove molding to use as a cut-depth guide for future workpieces.

If you plan to make more coves with the same setup, cut off a small piece at the end of the finished cove molding to use as a cut-depth guide for future workpieces.

With the cove done, examine its surface and sand as necessary to remove the angled blade marks.

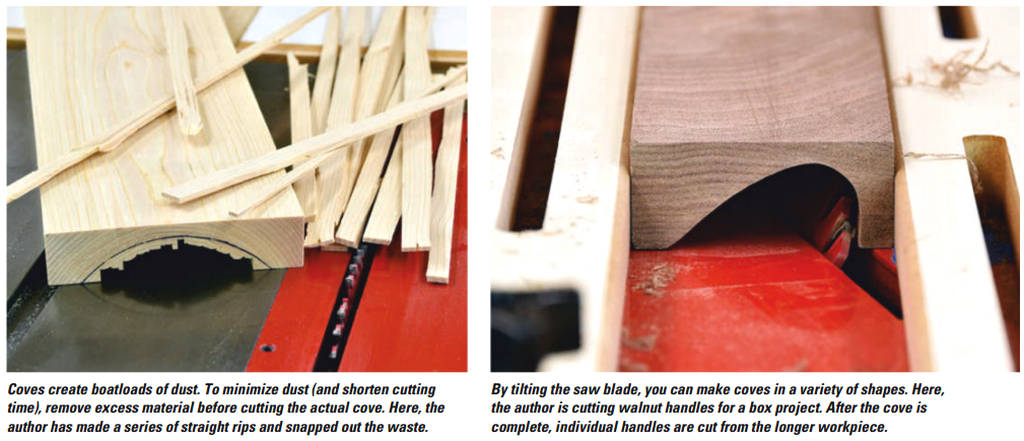

Cove cutting is a dusty operation. There are no scraps or offcuts produced with coves.

It’s all dust. Even with a good dust collection system, you can cut down on the mess by removing the bulk of the waste before actually cutting the cove.

In the above left photo, you can see that I prepped this workpiece by making a series of straight rips in the cove’s waste area. With each cut 1/8″ or so apart, it was easy just to snap the waste out in strips. This not only eliminates a lot of dust, but it also speeds up the process and makes for easier feeding, especially in hardwoods.

In our example, we’ve cut a symmetrical cove, but as noted earlier, you can cut almost any cove shape by tilting the blade. A symmetrical cove’s arc apex is in the center, but angling the blade shifts this apex to the side. The greater the angle, the farther to the side the apex will be. You can see what I mean in the photo.

Getting a specific cove profile can take a lot of calculation or some trial and error. You’ll find numerous charts and calculators for the process online, but I personally prefer just trying various setups and picking the one I like best.

Non-through Cuts

Cutting wide channels partway through wood — often called non-through cuts — are useful for rock-solid joinery. Called a rabbet when the cut is on an edge, a dado when it crosses the grain or a groove when it follows the grain, you can make these non-through cuts in a variety of ways. Router tables and shapers excel at this, and you can even cut them — albeit more slowly — with a regular blade in multiple passes. But most woodworkers agree that a dado set, sometimes called a “dado stack” or “dado head,” is the best way to go.

The set consists of two outer blades that resemble regular blades, which cut and define the edges of a dado, groove or rabbet. A selection of narrow chipper blades with fewer teeth clean out the waste in the center of the cut, between the outer blades. Rounding out the set are shims and spacers in various thicknesses. How you “stack” these together determines the width of the cut. Manufacturers often include a simple chart listing the needed components for typical cuts.

Install the dado set one piece at a time, starting with an outer blade. Chippers and spacers follow as needed for specific cut sizes, with the other outer blade going on last, and the arbor washer and nut holding everything together as a unit. By the way, dado sets are smaller in diameter than standard 10″ blades. A 10″ table saw, for instance, uses an 8″ dado set. You’ll also need to remove the riving knife, which not only impedes the cut of the smaller diameter dado blade but also serves no purpose for non-through cuts.

Some table saw throat plates have openings that accommodate narrow dado blade widths, but some don’t. If yours doesn’t, you can make your own throat plate out of MDF or plywood, using the same process for making any zero-clearance insert. As a bonus, a custom plate improves dust collection and helps eliminate tearout.

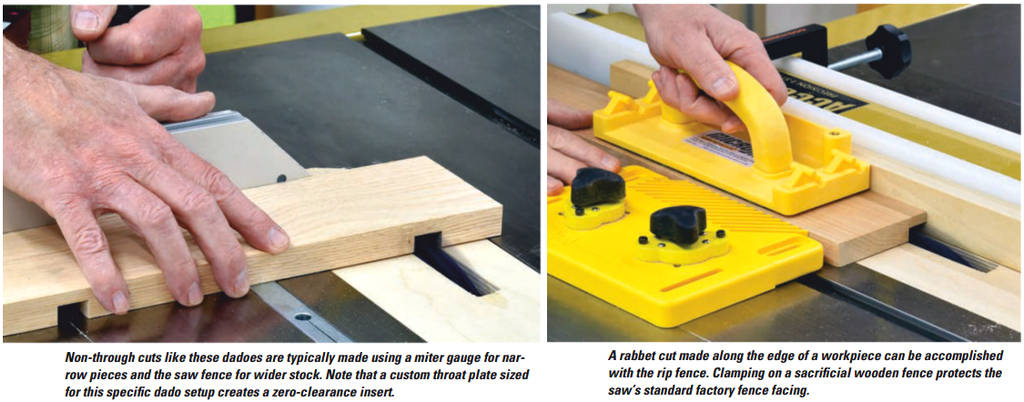

You can cut dadoes, grooves or rabbets in large workpieces using your table saw’s rip fence, just as you would for any rip or crosscut in large stock. For narrow workpieces, a miter gauge is your best bet.

You can cut dadoes, grooves or rabbets in large workpieces using your table saw’s rip fence, just as you would for any rip or crosscut in large stock. For narrow workpieces, a miter gauge is your best bet.

For cutting rabbets along an edge, all you need is your rip fence. However, you’ll first want to add a sacrificial fence. This can be any piece of straight stock, simply clamped to the face of your regular fence. This allows you to adjust it until the fence facing just kisses the blade, making for smooth, accurate rabbets.

As with other non-through cuts, your hands will often pass right over the blade. So be sure to use featherboards and push blocks for safety.

Cutting Tapers

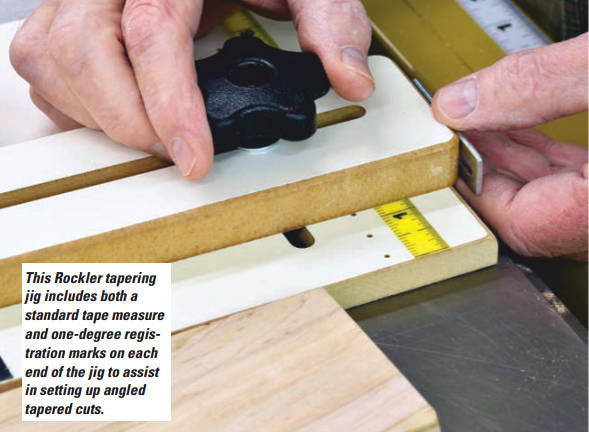

Taper cuts are nothing more than angled rip cuts. You can cut simple tapers with a jigsaw or band saw, then refine them with sanding or planing. But for more accurate, repeatable results, a taper-cutting jig is faster and easier. These jigs, such as the Rockier Taper/Straight Line Jig shown here, are essentially variations of crosscut sleds that use your saw’s miter slot to guide them.

In addition to the base, which has a miter bar on the underside, the jig consists of a moveable fence to set taper angles, hold-down clamps to secure the workpiece and a handle. Index marks, set at 1-degree increments, and tape measures at each end, help align everything. An adjustable workpiece stop caps the end of the movable fence.

In addition to the base, which has a miter bar on the underside, the jig consists of a moveable fence to set taper angles, hold-down clamps to secure the workpiece and a handle. Index marks, set at 1-degree increments, and tape measures at each end, help align everything. An adjustable workpiece stop caps the end of the movable fence.

To set up the Rockier jig, first size it to your saw. This is simply a matter of assembling the jig and running it through the saw to cut a zero-clearance edge along the jig’s base. With the tape measures then applied right at the new edge, precise angles are easy to set.

Let’s cut a small table leg that’s tapered on two sides. First, mark the “foot” end of the leg where the taper cuts end (see top left photo). Then pencil lines around the upper part of the leg where the tapers begin.

To mount the workpiece in the jig, align the pencil lines designating the top and bottom of the taper with the jig’s zero-clearance edge, snugging the fence in place against the workpiece and twisting the knobs to lock it down. To secure the workpiece itself, swing the hold-downs into place and lock them down.

To make the cut, raise the blade so it clears the top of the workpiece, turn on the saw and feed the jig through the cut. Once the first taper is cut, disengage the hold-downs, rotate the workpiece 90 degrees, secure it once again with the hold-downs and make the second cut. You’re done.

Tapering jigs can also function as straight-line jigs, perfect for processing rough stock or workpieces with irregular edges. For this, remove the miter bar and use the saw’s rip fence for guidance instead. Set the jig’s movable fence as needed to support the work-piece, and use the hold-downs to secure it. As before, use the jig’s rear workpiece stop to support the end solidly.

Set the saw fence to the appropriate position to make the cut, then feed everything through just as before. Now your workpiece has a fresh, straight edge allowing you to further process it however you like.