How to diagnose problems and get the best results from one of your most useful machines. Story by David Luckensmeyer.

Bandsaws are one of the most versatile machines in the shop. So it’s worth taking time to troubleshoot any problems, especially if yours docs not perform like it should. Whether you’re undertaking restoration work, or tweaking and calibrating a new machine, there’s something here for everyone.

I often field questions like, ‘Which bandsaw should I buy?’ or ‘What’s best for resawing?’ Invariably I recommend purchasing used. Older bandsaws are generally heavier and better built machines for the same money. But you also need to know the anatomy of a saw, how to diagnose issues, and the general setup for fine work.

Eliminating vibration

Vibration is an enemy of smooth cutting and there are potential sources that need to be identified: frame, motor, bearings and wheel balance.

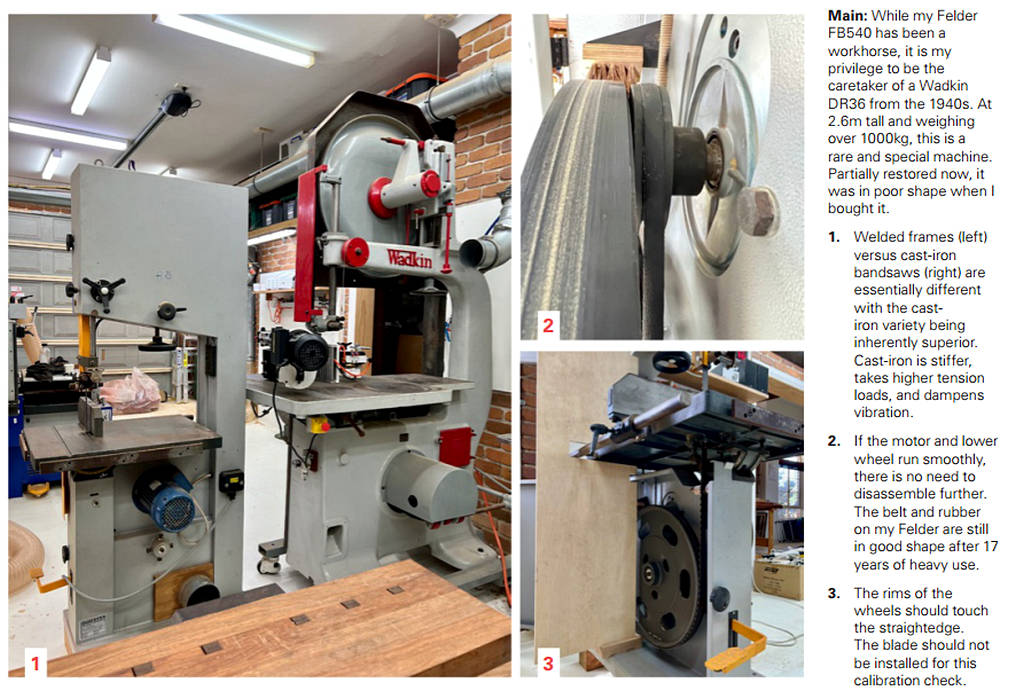

Examine the entire machine carefully. Casting damage and welding cracks mean the saw will not tension a blade which will flutter and wander. If a visual inspection fails, the saw is usually not worth buying or keeping (photo 1).

Disassemble the main components of the machine to isolate the motor: remove the blade and drive belt/s, and if direct drive, consider removing the lower wheel. The motor should run quietly and smoothly. For safety, disconnect the machine from power after running.

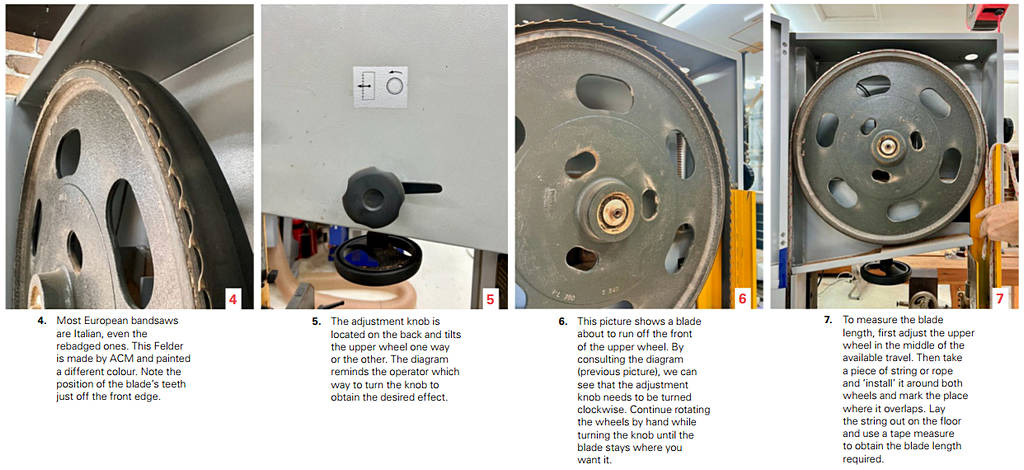

Before putting the belt/s back on, grab each wheel with both hands and give it a proper tug (static check), and spin by hand (dynamic check). Look for side-to-side movement and listen for bearing noise (e.g., grating, clicking). The wheels should rotate for quite some time, and come to a complete stop. A momentary reversal of direction indicates a wheel balance issue (photo 2).

Let’s assume at this stage that your machine runs with little to no vibration.

Wheel alignment and wheel rubber

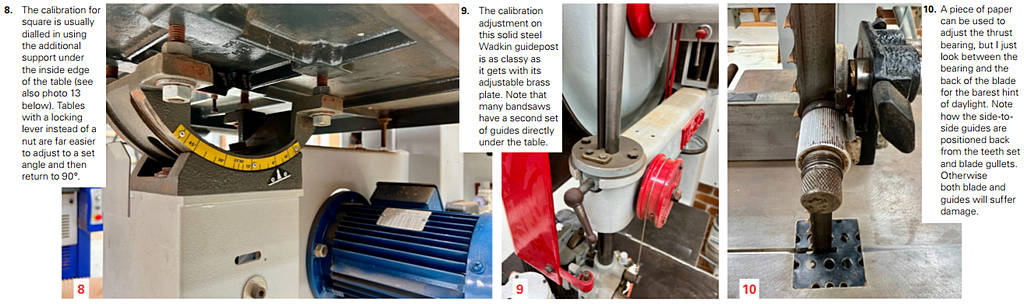

The upper and lower wheels must align in the same plane or the blade will not track properly. The best way to check for alignment is to place a straightedge directly against the top and bottom wheel rims.

If the machine chassis and cast-iron table arc in the way, take a piece of plywood and straighten one edge on a slider or with a track saw. Notch the edge to accommodate the impeding parts of the machine. In general, only the upper wheel is adjustable and those adjustments arc machine specific (photo 3).

American-made bandsaws and Chinese clones usually (but not always) have slightly rounded or domed tyres. The dome is designed to help centre a bandsaw blade and allow for teeth set. European bandsaws have flat tyres. Such wheels are designed to run a blade’s teeth off the front edge of the wheels to allow for teeth set (photo 4).

Tyres with deep grooves, undulations, or missing chunks need replacement. Chris Vesper in Melbourne offers this service. Very few do, as the wheels must be rebalanced perfectly before use. For less serious degradation, the rubber can be sanded smooth. But I won’t get into that here.

Blade tensioning and tracking

The upper wheel is mounted on an arbor which is adjustable vertically (blade tension) and for tilt (blade tracking). The adjustments arc usually via knobs or handwheels (photo 5).

Before installing a blade, back off all guides (above and below table) so that nothing impedes the tracking adjustments. Tracking can change as the blade is tensioned.

Apply moderate to full tension on the blade. By ‘moderate’ I mean enough so that the blade docs not exhibit much deflection when pushed from the side.

Most machines also have some way to register the tensioning level but in my experience it serves as a relative guide only. Slowly rotate the wheels by hand and watch for lateral blade movement (towards the front or back of the wheel: photo 6).

I like to rotate the wheels up to a dozen times by hand to satisfy myself that the blade is tracking properly. Turn on and immediately turn off the machine as a final check that the blade is running true.

While blade choice is often the last topic to be addressed, my instructions relating to the trunnion, table and guides, require a properly fitted blade. Cheek the blade weld. There should be no clicking sounds through the blade guides, and no visual movement between the back of the blade and the thrust bearing. I find inexpensive carbon blades arc fine for most curved and joint work.

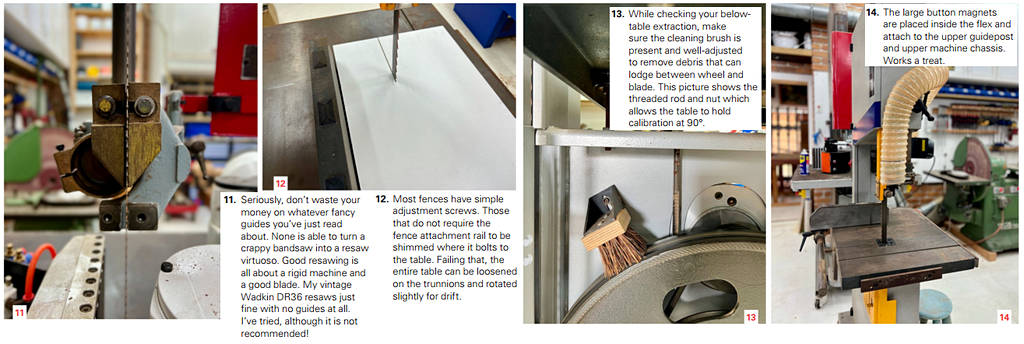

However, a more discerning choice is warranted for resaw work. My favourite resawing blade is the Woodmastcr CT 1.3TPI made by Lenox. It is cheaper and cuts faster than the premium Lenox Trimastcr, which is a carbide band. I have extensive experience using both to resaw Australian hardwoods and exotics. Some of my colleagues also report good results with the Laguna Resaw King (photo 7).

Trunnion and table

Table checks can only be accomplished once the other calibration processes above have been completed. Otherwise, you’ll be doing them again.

Unfortunately, the trunnions on most bandsaws are weak. Make sure the table bolts/ nuts arc tight and any adjustment for tilt is working adequately. Some tables arc not flat and have twist and hollows (or both). If there’s a problem, it is possible to install a sub-table with appropriate shims. But let’s assume your table is reasonably flat.

Calibrating your table for square means you can trust your bandsaw for precise cuts. Remember, checking the results of a cut is always more accurate than checking the blade itself. For left-to-right table adjustments for square, the trunnions and table support (if present) can be tweaked. Front-to-back ‘squareness’ is harder to dial in and involves inserting shims between the trunnion attachment points and the underside of the cast-iron table (photo 8).

Guidepost and guides

The guidepost carries a thrust bearing that provides support at the back of the blade, and ‘guides’ on the left and on the right of the blade. It consists of a vertical ‘arm’ or ‘post’ that can be adjusted up and down depending on the thickness of timber being cut.

Cheaper, modern saws have flimsy posts that do not remain calibrated when moved. Look for machines with robust guideposts that have the ability to be aligned in all directions.

Calibrating the guidepost is machine specific but typically there is a locking lever for vertical adjustment. Machine plates usually ‘rub’ against the vertical guidepost with adjustment slots and bolts/screws for alignment. Aim for a perfect vertical alignment with a tensioned blade (photo 9).

The support at the back of the blade can be a thrust bearing, a hardened metal disc, an edge-oriented bearing, or a ceramic block. Best practice calibration is to adjust the support as close to the back of the blade as possible but not touching (photo 10).

Side supports likewise come in many varieties.

European machines usually have two facing bearings that arc typically good at supporting larger blades from twist. Carter style bearing guides arc popular and reasonably easy to adjust. Lenox style ceramic blocks arc also generally well received. Even hardwood timber blocks will do just fine. Take care to adjust the guides equally so there is no lateral deflection of the blade. Again, close but not touching (photo 11).

Rip fence, mitre gauge and drift

Drift is a minor problem which has been overblown as an opportunity to upsell fancy (and often expensive) aftermarket fences and mitre gauges. I would suggest spending your money on a better blade.

Significant drift – the tendency for a blade to wander consistently one way or the other – indicates a setup problem: under-tensioned blade, mis-aligned wheels, blade damage or even just a bad blade with uneven teeth set.

Minor drift is common. To determine drift direction, take some scrap with at least one straight side, mark a line parallel to the straight side, and make a partial cut (say 100mm) along that marked line. Take special care to follow the line exactly. Leave the blade in the just-cut kerf and turn off the machine. Now bring the fence alongside the scrap and adjust so that the fence is parallel with the straight side of the scrap (photo 12).

I do not find a mitre gauge necessary on a bandsaw. For breaking down long boards into shorter lengths, I just cut by eye and move on. For shoulders and other joint work, a dialled in fence works very well.

Dust extraction

Most bandsaws have below-table dust extraction ports, and sometimes two. Such extraction collects the larger chips carried downward in the blade kerf and keeps the lower wheel housing clean. A compressed airgun is handy for clearing away any larger chips that escape above-table (photo 13).

The generation of fine dust is more concerning and bandsaws spew plenty of it. Anyone who spends an hour resawing hardwoods into shop-sawn veneers will attest to that.

I’ve tried a number of solutions but nothing works better in my experience than above-table dust extraction and I would encourage you to implement such a system on your machine. It docs not have to be fancy. I use large rare-earth button magnets to keep the flex in place (photo 14). This solution is, well, ‘flexible’ when adjusting the guidepost!

Last words

This story has been about troubleshooting. I didn’t explore resawing techniques nor how to get the most out of your machine. For those topics, I strongly recommend the advice of my colleagues Darren Oates (AWRU64) and Damion Fauser (AWRU98).

Some of you may hold fears about buying ‘old and rusty’. I certainly did. But a bandsaw is one of the best machines to take the plunge because the anatomy and setup are simple. And the rewards of ‘old steel’ arc worth the extra time and effort. Have fun and be safe!

Photos: David Luckensmeyer